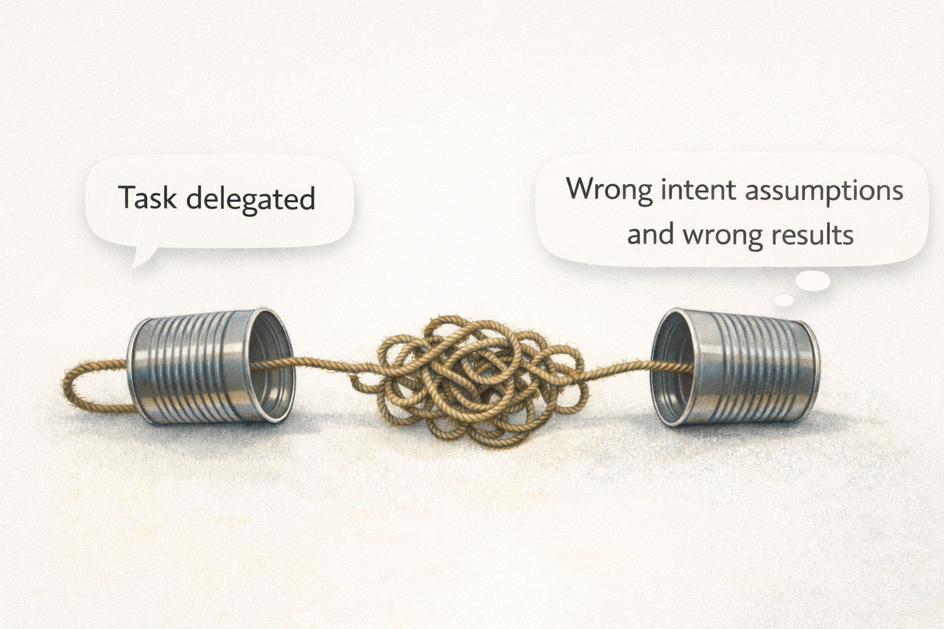

A while back, I delegated something I thought wa`s straightforward:

“Can you share a quick update doc by EOD?”

What I got back was excellent writing… but completely useless document for the decision we were trying to make. It wasn’t incompetence. It wasn’t lack of effort. It was something subtler:

the message didn’t survive the handoff.

That’s the Delegation Telephone Game (also known as Chinese Whispers):

Where the intent starts crisp and ends up slightly mutated after passing through different brains, different defaults, and missing context.

Delegation is a lossy form of communication

In the telephone game, the message starts crisp and ends mutated. That’s not a moral failing. It’s physics.

Even the plain description of the game makes the core point: errors accumulate as the message is retold, and it’s widely used as a metaphor for cumulative error as rumours or information spreads.

Delegation behaves the same way because it’s not “sending work.” It’s sending intent—which is always bigger than the words you typed.

When you delegate, the receiver has to reconstruct your mental model from partial inputs:

- What’s the real goal?

- What quality bar is implied?

- What constraints are non-negotiable?

- What’s “out of scope” even if it looks related?

- What does “done” mean for this audience?

If you didn’t write it down, they will still answer those questions—by guessing.

And the more hops your work takes, the more “telephone game” it becomes.

A Mathematical Theory of Communication

While researching for this article I arrived at this paper: A Mathematical Theory of Communication

The author framed communication in a way that feels unreasonably relevant to delegation:

“The fundamental problem of communication is that of reproducing at one point either exactly or approximately a message selected at another point.”

That’s delegation.

You’re trying to reproduce what you mean in someone else’s head (or in an LLM’s output) over a noisy channel: missing context, time pressure, different defaults, ambiguous language.

So if you treat delegation as “I said it once, job done,” you’re basically hoping the universe is lossless.

It isn’t.

Humans and LLMs fail in the same way: they fill in the blanks

This is the part that surprised me most when I started using LLMs seriously:

LLMs don’t just follow instructions. They complete patterns.

So when your prompt leaves gaps, the model fills them with plausible assumptions.

Humans do the exact same thing.

- Humans fill gaps with experience, norms, “what my manager usually wants,” and whatever seems reasonable.

- LLMs fill gaps with training priors and generic best practices.

Same shape. Different engine.

So whether you’re delegating to a teammate or prompting an LLM, you’re fighting the same enemy:

Unstated assumptions.

The unstated assumptions are what break the deal

Delegation rarely fails on the main idea. It fails on the invisible defaults.

The “quick update doc” example? Hidden assumptions were doing the damage:

- I meant: 1 page, decision-ready, bullets, risks + asks.

- They assumed: narrative recap, detailed context, polished writing.

Both outputs are “good.” Only one is useful.

💡 The fix isn’t “try harder.” The fix is to engineer communication.

Engineering communication: treat delegation like a protocol, not a vibe

If delegation is a lossy channel, then your job is to add structure that keeps meaning intact.

Not more meetings. Not longer messages.

Just a better “packet.”

Here’s the lightweight spec format that works for both humans and LLMs:

The Delegation Spec

- Outcome: What does “done” look like in one sentence?

- Why: What decision does this enable / who is it for?

- Constraints: Must / should / must-not

- Acceptance checks: How we verify correctness

- Checkpoint: Draft/POC first, then final

That’s the entire trick: reduce interpretation space.

Because this rule is undefeated:

The vaguer the delegation, the more room for wrong assumptions.

Why Analysis docs before starting the project are important?

Because they make the assumptions speak (before they become rework)

It works because it flushes out the defaults early, when changing course is cheap.

For humans, it reveals mental model mismatch.

For LLMs, it reveals silent priors before the model builds an entire answer on them.

What assumptions look like in practice

- “I’m assuming we can change schema” (maybe you can’t)

- “I’m assuming this is for leadership” (maybe it’s for implementers)

- “I’m assuming we care about speed over completeness” (maybe accuracy is everything)

- “I’m assuming we can ignore edge case X” (maybe X is the whole point)

Once assumptions are explicit, you can approve, reject, or refine them.

That’s engineering.

Break tasks down so they survive handoffs

Agile folks have a dozen mnemonics for writing “good tasks.”

INVEST is one mnemonic for what “good” tasks look like:

- Independent: can be picked up without a web of dependencies

- Negotiable: the approach can change; the outcome stays clear

- Valuable: it’s tied to a real outcome, not busywork

- Estimable: if you can’t estimate it, it’s probably not understood

- Small: small enough to review early (so drift doesn’t compound)

- Testable: you can tell if it’s done without a debate

Useful—but the deeper point is simpler:

Smaller, testable, independently meaningful tasks are harder to misinterpret.

When a task is huge, it becomes a story people can tell themselves in multiple valid ways. When it’s small and testable, drift shows up fast.

So instead of delegating:

“Implement the notifications feature”

Prefer something like:

- “Draft the API shape and 3 example payloads (include error cases).”

- “Implement the happy path for one notification type with tests.”

- “Add idempotency + retries; document failure modes.”

Each piece has clearer boundaries and clearer “done-ness.”

You’re not just planning—you’re designing work so a teammate (or LLM, or future you) can pick it up mid-stream without summoning your full context.

Plan your own work like you’re delegating it

This sounds weird until you feel the pain once:

Your future self is basically a stranger with your calendar.

Context evaporates. Priorities shift. You get pulled into something urgent. You come back later and think:

“Why did I do this? What was I trying to achieve?”

So write tasks as if someone else might pick them up—because eventually someone will. Even if it’s you.

This is what “engineering communication” looks like when you’re just planning your day.

What this looks like in real delegation (a quick before/after)

Before (vague):

- “Can you look into the latency issue and fix it?”

After (engineered): Maybe over-engineered for the blog but I am being explicit to not lose the intent 😉

- Outcome: Identify top 2 latency contributors and propose a fix with expected impact.

- Why: We need to decide whether to scale infra or optimize query path.

- Constraints: Don’t change user-facing semantics; no major refactor this week.

- Scope: Focus on p95 API latency for endpoint X; ignore background jobs.

- Acceptance checks: Before/after p95 numbers + a short write-up of methodology.

- Checkpoint: Share findings + plan by tomorrow 4pm; implement fix by Friday.

Same person. Same effort. Dramatically less drift.

Close: stop trying harder—design better handoffs

If your delegation keeps “almost working,” it’s probably not a people problem.

It’s a channel problem.

And domains with real consequences have learned: you don’t fix this with effort—you fix it with engineered communication.

So the message is simple:

The fix isn’t “try harder.” The fix is to engineer communication:

- make outcomes explicit,

- surface assumptions,

- define testable “done,”

- and add a fast playback loop.

That’s how you delegate to humans without rework—and work with LLMs without confident nonsense.